Hayao Miyazaki, the beloved helmsman of Studio Ghibli, is a titan of environmental media. His movies, from Princess Mononoke to Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, are critical films centered around themes of nature and sustainability. Almost every environmentalist I know has been profoundly affected by his work and his art has inspired countless activists, scientists, and other changemakers seeking to forge a better future.

As a practical guide for environmental conservation, however, some of his films miss the mark (spoiler warning for Pom Poko and Only Yesterday).

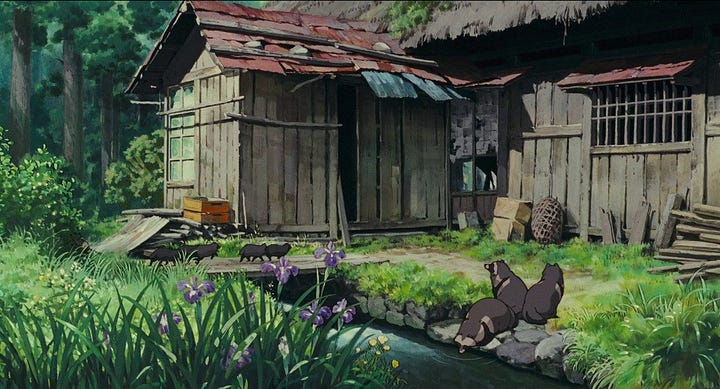

Pom Poko is one of my favorite movies. It focuses on a cadre of forest spirits attempting to protect their humble home from the onslaught of a housing development. Their haunting of the construction workers and sabotage of equipment is hoped to delay and eventually stop the development.

From the character’s point of view, the defense of the forest is clearly in their best interest. However, from the point of view of the wider environment, I would argue that the development was, in the end, better.

The housing development being built in the film was dense and transit-oriented. This is the exact type of housing we need to be building!! Dense urban areas are the least resource-intensive living possible. Residents can share water, sewage, HVAC, and electrical infrastructure, reducing the total resource use per person.

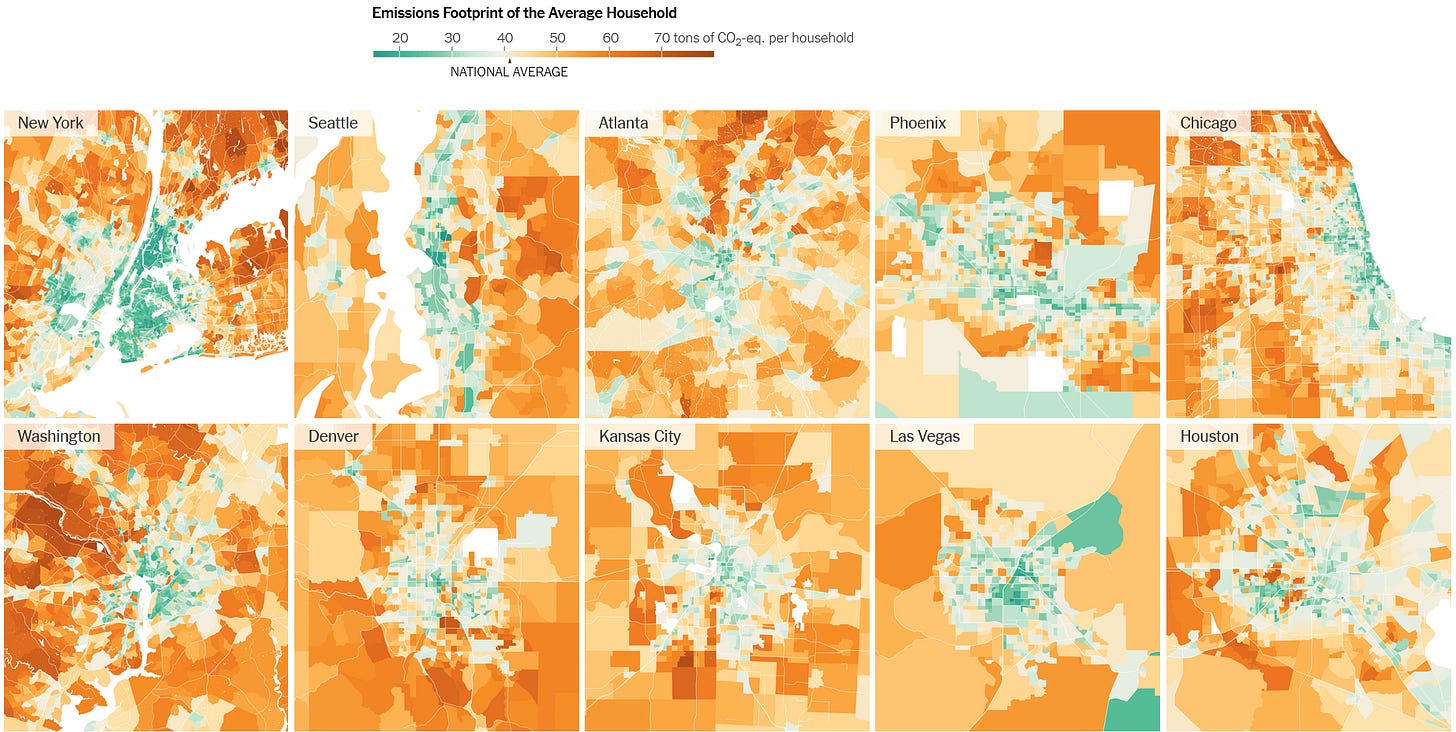

Dense housing also allows for more transit-oriented mobility, replacing a car-centric model typical of suburban development, which further reduces resource consumption. Our suburban model of housing is one of the reasons why North Americans are some of the biggest per capita emitters of carbon. Mixed-use urban areas also allow for people to have shorter commutes to the office or to run errands, further cutting emissions. Additionally, by building denser housing the total land footprint of a city can be much smaller, preserving more forest for the spirits.

The other Ghibli movie that caught my eye was Only Yesterday. This film follows a young woman as she takes time off from her stressful city life to go work on a farm picking safflower, perfectly capturing the disaffection of the urban worker and the desire to escape to the countryside. No notes on this plot, as I found this to be accurate to the feeling that many in my own social circle hold and is prominent in our generation given the popularity of the cottage core movement.

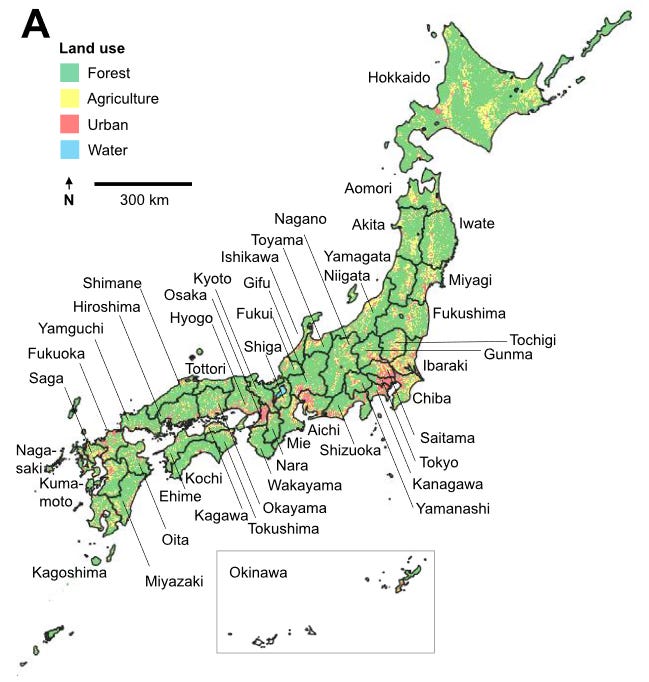

My gripe with this movie, however, is the uncritical advocacy of straightforward organic farming. Organic is a great philosophy, but by itself, it’s not going to meet human needs for food production. Half the planet relies on synthetic fertilizers for their calories and to meet those food needs organically, we would need to massively increase the amount of land in production. If the Japan of Only Yesterday all followed the farming practices of Toshio they would need to clear-cut large swaths of forest to make up for lost output. Modern-day Japan has many vast tracts of forestland largely because they farm a small portion of their land and import food from more productive nations that grow larger amounts of food per acre than poorer Japanese soils are capable of.

It is clear that we need a more sustainable form of farming, and Japan has been the source of several key movements and methods that have advanced a sustainable transition. I love the message of how farmers can use nature as a tool instead of fighting against it. But the film advocates a straightforward “return to tradition” instead of the integration of more sustainable, yet still productive, practices. And I’m not saying that I want a fully fleshed-out agronomic plan from the movie, more that the vision of the movie is out of line with what the scientific literature shows is the best path forward for sustainable agriculture.

Art is critical to inspiring and driving change. Stories allow us to explore a range of perspectives and experiences and allow us to critically evaluate the world as it is and imagine better futures than our present. Art has its limitations, however. Good art needs a strong narrative and aesthetic attraction. This necessity can bias how we view what is ‘good’ for the change we wish to realize. Environmental art leans on sweeping views of untouched landscapes, idolizing a quiet life in the country eating locally grown food, and wearing locally spun wool. In reality, those who live in urban areas have by far lower carbon emissions, and the global trade in agricultural products adds almost nothing to the emissions associated with those goods. These are concepts that are easy to display through data but are difficult to translate into art.

In confronting complex challenges, art is best contextualized as a vision over a roadmap. Stories exist in a world of exaggeration where who is good and who is bad is clear and the mission is straightforward. A cohesive energy policy is never going to come from art.

Ultimately, the films of Miyazaki and similar storytellers still do way more good than harm. I didn’t grow up with Studio Ghibli, but movies like Hoot (far less cinematic than Spirited Away) led me to become an environmentalist and dedicate my career to pursuing a more sustainable future. We are in desperate need of hope and imagination, and artistic movements are working to build values of urbanism and innovation into how we conceive of a green future. We just need to remember that art will never fully map onto reality.

What I’m Reading, Watching, and Listening too

6 Reasons Why Personal Finance Gurus Are Wrong: An evergreen reminder.

A Post-Google World: As the search giant faces an onslaught of anti-trust lawsuits, what does a world where the world’s fourth most valuable company is broken up look like?

Why recipes are holding you back from learning how to cook: A call for closing the cookbook and becoming comfortable with experimentation.

The thermodynamics of electric vs. internal combustion cars: Why an electricity-driven world will be more efficient than a fossil-driven one. This fact is critical to the energy transition.

Are you aware of the Ghibli-inspired Chobani commercial ( https://youtu.be/z-Ng5ZvrDm4? )? I'm not sure how much to believe in that vision but it sortof paints a mixture of the aesthetic with (small-scale?) precision ag, geoengineering, and other modernities and urbanism in the distance.

Again, I find myself rather questioning about such visions out of concern they lead to techno-optimism over understanding ecological limits but an interesting thing to note as it spread in various social spaces such as the solarpunk movement. Another image I often see spread in ecofuturism is https://www.jessicaperlsteinart.com/workszoom/3667292/the-fifth-sacred-thing#/ , which still feels a bit contrived to me but perhaps I've seen the artwork reused in event announcements and newsletters so many times.