Is Actual Nature Necessary to be Connected to it?

A rambling rumination on landscapes and the mind

Recently, I came across a neat little tool called NatureScore. You input your address and it returns a score of 0-100 and a little blurb evaluating how much nature surrounds your location. For example, my apartment in Columbia, MO has a score of 76.6, which is regarded as “Nature Rich.” Given how my apartment is right against a woodland and well-shaded by a number of sturdy oaks, I’m inclined to agree.

I would take this service with a couple of grains of salt, however. It gave my old apartment in Ames, IA a score of 85.3, despite it having far less greenery than my current place. It was situated near a walking trail, but that took a little bit of time to get to. Regardless, this seems like a cool tool with a decent amount of utility in assessing urban spaces for green scenery and recreation.

However, I then decided to turn my attention to my family farm where I grew up. Our farm is smack dab in the middle of a cornfield, with a small windbreak of pine and spruce bordering the acreage. Being one of the most modified landscapes in the world, it is not natural by almost any definition. And yet, the farm received a whopping 95.4; designated a “Nature Utopia” by the service.

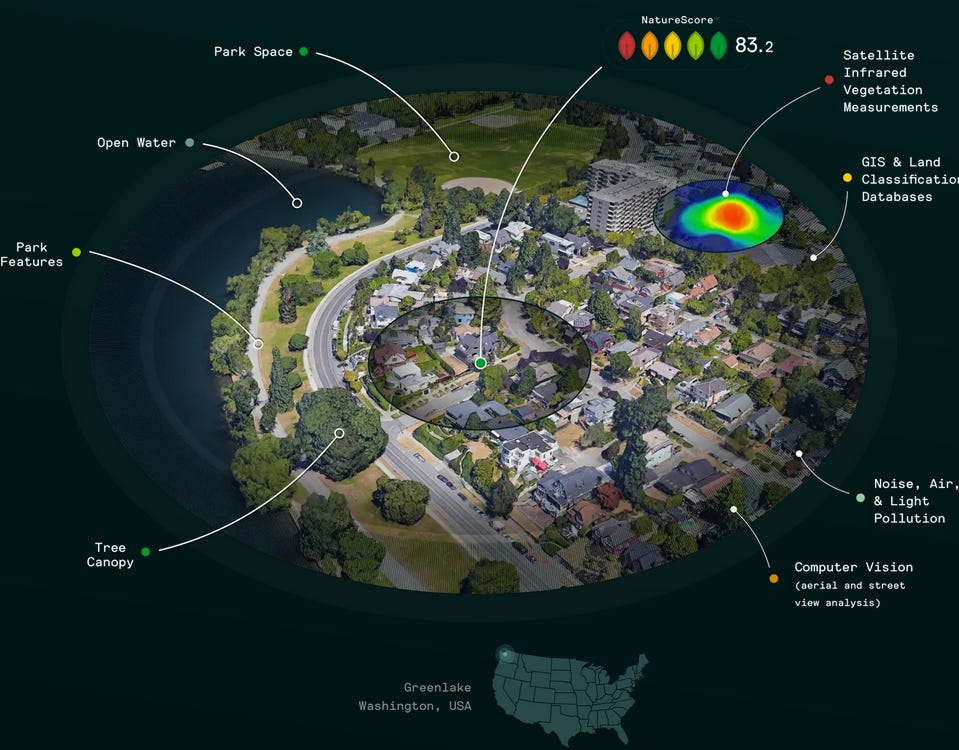

I would not call this landscape a “Nature Utopia.” Corn country has its aesthetic charms. Sunsets over a tasseling cornfield or a dewy morning gazing upon a soybean field are their own form of beauty, but natural they are not. Looking over how the NatureScore is calculated, it seems to be an aggregation of “satellite infrared measurements, GIS and land classifications, park data and features, tree canopies, air, noise and light pollutions, and computer vision elements.” These data streams are optimized to showcase nature in specifically urban areas and have limited usefulness in rural areas. They show vegetation, not necessarily nature. The calculations they use seem to mistake miles of monocultured cropland for a nice treed boulevard or ample neighborhood parks.

However, this does raise a question for me. The whole point of this project is to help renters, homebuyers, community organizers, and city planners determine areas with and without vegetation as a public health mission. Landscapes with lots of natural elements, from trees to water features, are proven to have a host of psychological benefits. Feeling connected to the natural world calms our anxieties, lightens our sadness, and aids us in healing and growing. For residents, finding urban living spaces with these qualities can be an important feature in home hunting. And for community leaders, prioritizing their development is doubly important for raising quality of life.

NatureScore is well suited to identifying areas carrying these benefits in urban areas, but I’m wondering if it is doing so in rural areas. Is the service correct in identifying my parent’s farm as a Nature Utopia? Even if it lacks the vegetative diversity or visual variety of the land surrounding my apartment, does that even matter? Do agricultural landscapes carry the psychological benefits of more traditional conceptions of nature?

Unfortunately, this doesn’t seem to be a well-studied topic. Most research seems to document psychological benefits in urban as well as properly natural spaces, often comparing the two as well as comparing urban areas with and without green spaces. The inclusion of agricultural landscapes, and the diversity of forms they can take, appears to be lacking in the literature.

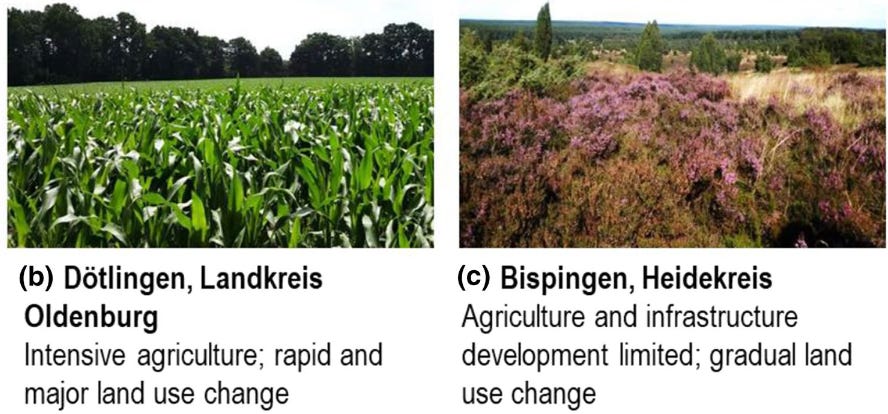

The one exception to this seems to be a paper by several researchers at Leuphana University in Germany. They compared rates of human-nature connectedness in two areas of Lower Saxony, one with an intensive and one with a more variable agricultural landscape. Overall, they found that the former was associated with much higher rates of disconnection from the natural world as well as reduced social cohesion and regional identity associated with a well-defined natural area. To me, this also implies that any psychological benefit coming from nature would not be present in this area.

I’m not sure that this represents the whole story, however. Growing up in corn country, people still view our intense agricultural landscapes as natural. Anecdotally, many people I know seem to be more at peace out in the country than they do in the city. And while a big part of this is certainly from the comfort of home, I think landscape plays a role. On the other hand, people I know who moved from a more forested area to places like my hometown have said the terrain feels drab and uninteresting to them. Whereas to me, despite my deep understanding of the ecological harm our farming practices cause, I still find a lot of peace in the amber waves of monocultured grain.

To me, this points to familiarity with a landscape being a major component of all this. Cultural lenses and upbringings matter. In Germany, there is a pervasive cultural ethos that forests are the ultimate form of a natural area. Forests are romanticized and deeply embedded in the cultural consciousness. The Grimm Fairy Tales took place in the stored Black Forest. This is partially why Germans are such avid hikers and prioritize urban green spaces. So it’s logical that when interviewed a bunch of Germans would find a cornfield alienating.

Heavily modified agricultural landscapes can also take on this sheen of cultural importance. The archetypical Irish landscape is a grassy, windswept hill where sheep graze on the abundant grass. A vision considered deeply ancient and traditional by both the Irish and international visitors. This scene is, however, an inaccurate view of what wilderness actually looks like in Ireland. And yet, many Irish folks would tell you their windswept countryside is just as calming and enriching as the thick Atlantic rainforest.

We tend to conceptualize ‘natural’ as places with a variety of trees, grasses, and flowers — forests, meadows, grasslands, etc with ample biodiversity. Intellectually, we understand that these are meaningfully different from a city park or a cornfield, however, I’m not sure it matters to our brains. The landscapes we grow up with, be they amber waves of grain, a city park, or a true wilderness, are still places which we can form attachments to the natural world. Places that heal and enrich our minds. A place does not need to be truly natural to bring us tranquility. Despite the many flaws of this land use, I believe corn and soybeans provide similar opportunities to connect with the natural world as trees and parks.

What I’m Reading, Watching, and Listening too

Was California’s Wine Revolution Just a Mirage?: A great piece examining how the business model of California’s wine industry is unraveling.

It was a classic rap beef. Then Drake revived Tupac with AI and Congress got involved: An analysis of our cultures history of using technology to keep key figures alive even when they’ve passed.