5 Changes I would make to Farm Policy

Agricultural policymaking in the United States is fundamentally broken. The incentive structure promotes maximal production while neglecting environmental or social outcomes. In a review of American agricultural policy since the Dust Bowl, economist Dr. Silvia Secchi showcases how conservation programs are geared towards providing additional farm income streams as opposed to serious improvements in environmental quality or the retirement of working land (Secchi, 2023). This regulatory regime is the primary driver of the many ills inherent to American agriculture, and serious reform is necessary.

Considering the sclerotic Farm Bill process, which was supposed to deliver a new policy package in 2023 and likely won’t be passed until the next administration, I thought I would discuss some of the reforms I would like to see made to U.S. agricultural policy. Some of these are major rethinks of the core USDA programs, while others are more novel ideas to fix moderate yet persistent issues facing agriculture. While I am not a policy scholar or law expert, I think these reforms would go a long way in fixing structural issues negatively impacting land, rural communities, and farmer pocketbooks.

Tax inputs, invest in nature

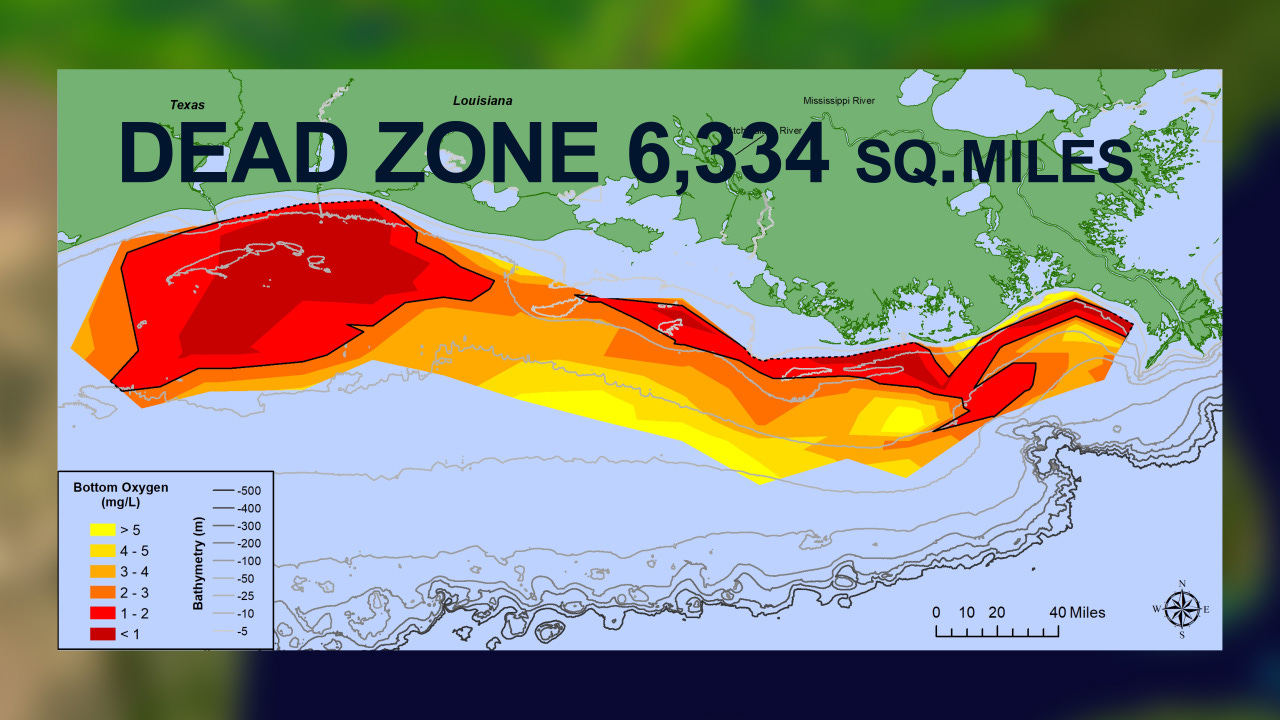

Chemical inputs: fertilizers, pesticides, and plastics, are fundamental to modern agricultural production. Nitrogen fertilizer alone is responsible for providing the calories for up to half the planet, and pesticides and plastics help to protect and strengthen crops in the field. These wonderous innovations come with heavy environmental costs, however. Fertilizer runs off into the water, causing immense amounts of downstream pollution and resulting in things like the Gulf dead zone, a massive patch of ocean that has been rendered virtually lifeless. Pesticides have had major consequences for insect and plant biodiversity, causing mass dieoffs of bees and having serious health consequences for workers and communities living near agricultural operations. And any conversation about pollution these days would be remiss to mention microplastics, which are a major consequence of modern plasticulture practices, particularly among horticultural operations.

Among economists, these situations are referred to as externalities. Inputs generate enormous profits for farmers who are able to achieve high yields. Despite being the main party that benefits from these practices, they are not the only party that has to deal with the consequences. The environmental costs are borne widely, while the profits are enjoyed by the few. Look at the city of Des Moines, which has had to spend millions on the world’s largest nitrate removal facility (Clayworth, 2023), despite most of the pollution being removed from the facility originating in agricultural areas outside of the city’s purview. Farmers upstream get to enjoy high yields and their associated profits whereas Des Moiners bear the cost with higher utility bills.

One of the primary methods used to deal with an externality is to tax the activity to either discourage it or raise funds needed to deal with the consequences. Many programs are funded this way, such as the Superfund environmental clean-up program, which is partially financed through taxes on petroleum and chemicals sales which are spent cleaning up sites damaged by those industries.

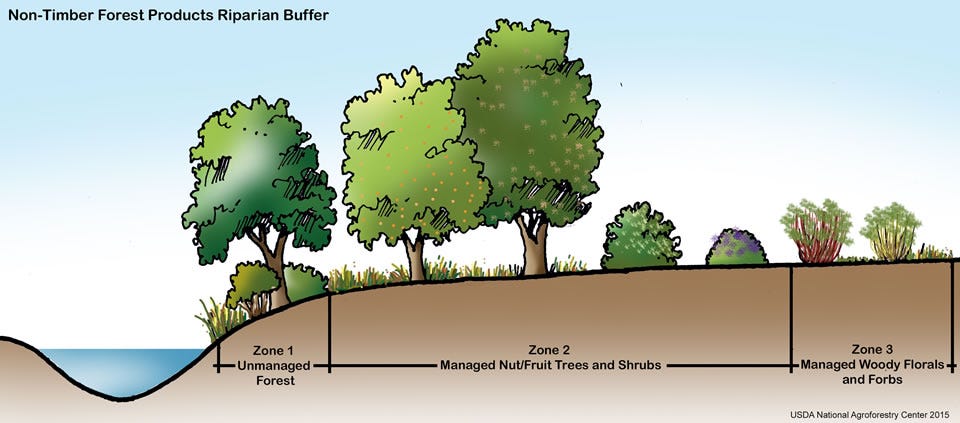

My proposal would be similar. Tax the purchase of chemical inputs and put those funds towards remediation and restoration programs. Fertilizer taxes should be used primarily to fund practices such as riparian buffer strips or waterways, which are plantings of perennial vegetation along watercourses to absorb excess nitrates from the water as it runs from the field to the stream. For pesticides, I would use the funds to restore habitat corridors in agricultural regions to provide habitat for native insects and plants. However I’m sure there are other strategies that would also be beneficial that I am not aware of that more directly address pollutants. For plastics, I’m not entirely sure what raised funds could be spent on to remedy this issue, but I’m hopeful that the microplastics researchers will be developing recommendations.

Tie subsidies with conservation

Subsidies are the lifeblood of American agricultural policy. The Farm Service Agency and Risk Management Agency administer an array of credit, loan, insurance, and grant programs that stabilize the finances of farms across the country. In my home county alone, just under $500 million in non-conservation subsidies have been issued since 1995 (Environmental Working Group, 2024). While these programs are important in stabilizing food prices and maintaining profitable farms, they incentivize farmers to maximize production at all costs, land degradation be damned.

Meanwhile, getting farmers to adopt conservation practices is an uphill battle. Pretty much any conservation practice is entirely voluntary, and to get any significant number of farmers to adopt improved practices requires additional subsidies on top of the existing regime to move the needle. Not only is this expensive, but once the contract ends farmers tend to stop utilizing the practice and return to destructive practices.

To remedy this situation, I propose requiring a baseline of on-farm conservation practices as a prerequisite to receiving subsidy payments. Farmers still have the right to farm the land as they see fit, but if they want the public to partially fund their operation, then the public should have a say in how the land and water are treated. Tying these requirements with subsidies creates appropriate incentives to improve environmental quality while making the program economically sustainable, as it doesn’t require continual budgetary appropriations. It also requires those who cause pollution to pay to remedy it.

This can take two forms: requiring specific practices or outcomes. The former would set specific requirements based on the crops a farmer grows and the region where they’re located. The latter would allow farmers to implement any practice they prefer, but they must maintain specified levels of erosion, runoff, and biodiversity. Prescribing practices have the advantage of reduced monitoring costs, whereas prescribing outcomes allow farmers to have more agency in the specific approach to achieving conservation goals. Ideally, banning egregious practices, such as winter manure applications or planting in 2-year floodplains, as a baseline while giving farmers leeway to accomplish broader environmental outcomes would be a ‘best of both worlds’ situation.

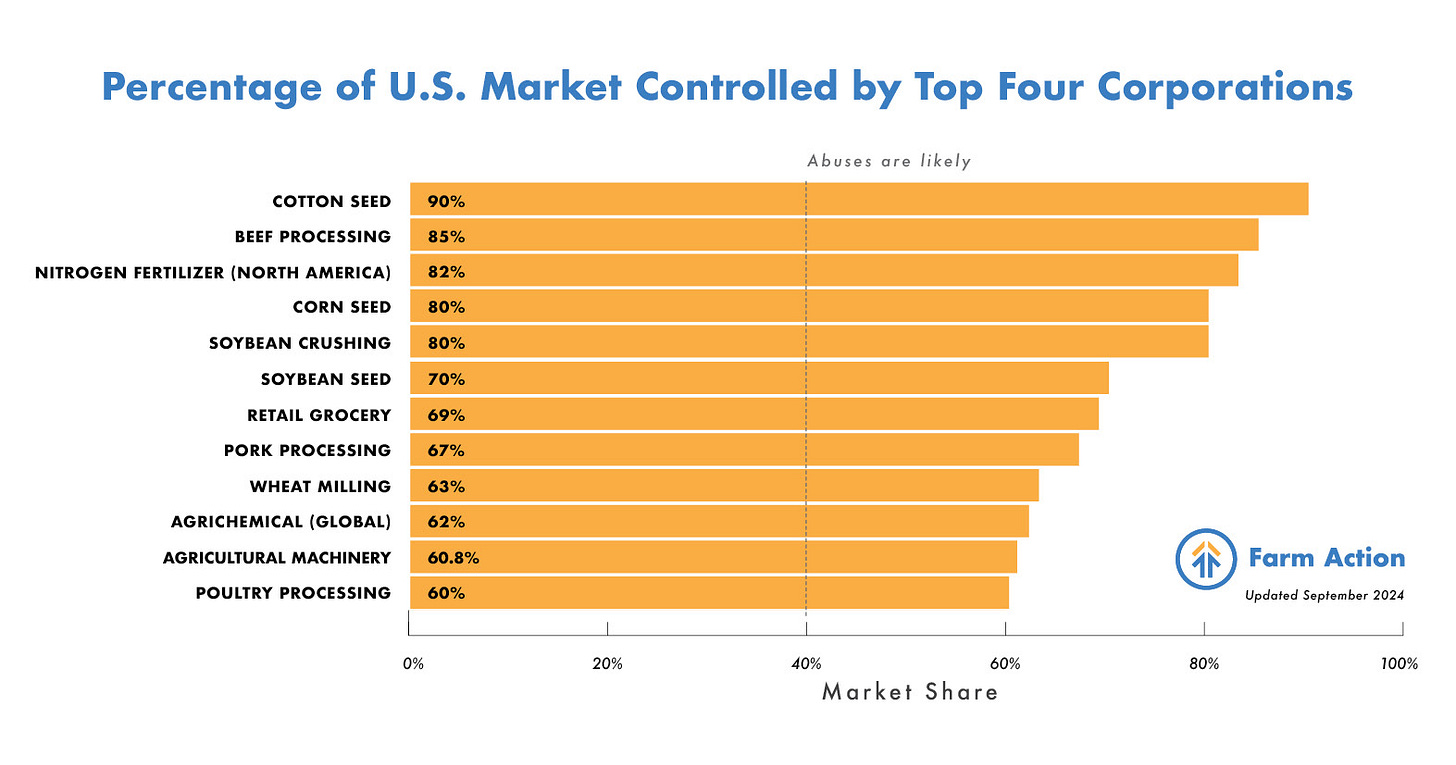

Break up monopolies

Another persistent issue facing American agriculture is the lack of competition. Farmers face monopolistic pressure from two fronts. On the supply side, the sellers of seed, machinery, and inputs are heavily concentrated in a few firms. For example, four firms control 84% of the corn seed market, another four control 82% of the nitrogen market, and three firms control a whopping 97% of the combine market (Farm Action, 2024)! Moreover, on the demand side, only a few firms are available to purchase crops and livestock once harvested. In the grain market, four firms control the purchasing of grain, and livestock producers are similarly locked into a few buying firms. Between supply and demand sits the farmer, lacking in any sort of market power and subject to the pricing whims and extractive strategies of multi-billion-dollar conglomerates.

There is a huge need to restore anti-trust enforcement in the agricultural sector. Under the Biden administration, there has been a resurgence of such enforcement driven by the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice (Stoller, 2020a). By rewriting merger guidelines, implementing new legal theories to go after monopolies, and simply letting regulators regulate, these agencies have helped stem the tide of mergers and sought new protections for consumers. This extends to agriculture, where the FTC has launched a lawsuit against pesticide manufacturers to stop them from strong-arming dealers from carrying rival products (Stoller, 2020b).

Most agricultural competition work in government these days is happening in USDA, and it is relatively incremental. It mostly focuses on boosting small and medium commodity buyers, such as local meat lockers, or by modernizing the Packers and Stockyards Act, a piece of legislation granting the agency powers to regulate meat markets (USDA Press Office, 2024; USDA-AMS, 2024).

This doesn’t go far enough. The food system is heavily concentrated, and it doesn’t just impact farmers. Consumers are highly exposed to these pricing strategies as well. Instead of incremental reforms and post-merger actions, the government should pursue the breaking up of individual sectors and, more importantly, decouple market segments from one another. Chemical companies should not produce seeds, for example. Breaking up conglomerates and introducing more dynamism to supply chains would reduce individual firm power and stimulate competition, allowing farmers to have more choice in who they do business with and the conditions they will accept with each new order or contract.

Additionally, strengthening farmer cooperatives and giving them more buying power would help tip the scales more in the direction of the farmer. However, this is more of a matter of organizing farmers and existing cooperatives to be more ambitious. More diverse markets, however, would go a long way in creating more opportunities for such ambition to bear fruit.

Crop diversity financing mechanism

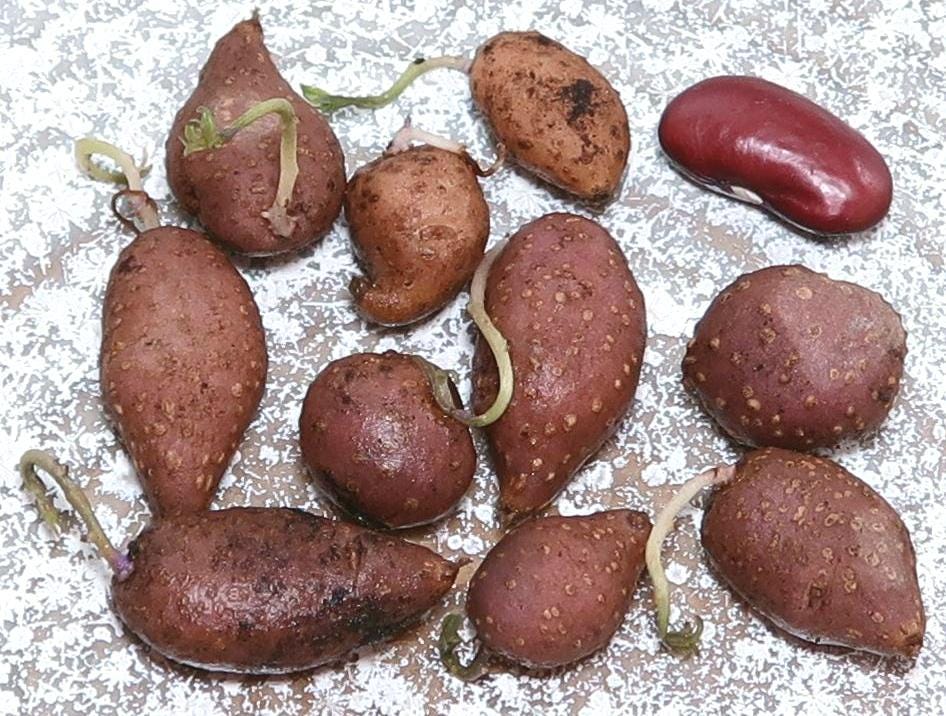

I’ve written about this idea before for the Post-Carbon Institute (Monaghan, 2023), but I’ll summarize and expand on it here. One of the long-term issues within agriculture is the low levels of biodiversity within cropping systems, which leaves us vulnerable to disease outbreaks and environmental stressors. There are two major programs necessary to build more genetic diversity into our crop populations. The first is the conservation of wild relatives or heirloom varieties of crops, such as wild apples or traditional varietals of rice, that contain potentially valuable traits that could be integrated into domesticated populations. Second, funding plant breeding programs to integrate these genetics into seed to ensure such genetics are accessible to farming and improve the resilience of our food supply. A good example of this in action is the preservation of traditional barley varieties in Scotland is allowing plant breeders to integrate salt tolerance into modern high-yielding varieties (Martin et al., 2023).

As it stands, crop genetic conservation is primarily funded by national governments, with some support from the nonprofit sector. While this is undoubtedly good, it has led to funding being left to the whims of legislative appropriations cycles. Establishing a more consistent form of funding for genetic conservation and public plant breeding programs is incredibly important for the future of our food supply, especially since funding for this work has lagged in recent decades. It would also help to make more seed available in the public domain since most plant breeding is done by private corporations.

Fortunately, there is already a model for this! Checkoffs are a system where farmers pay a small fee for every unit of a commodity they produce. These fees fund various research and marketing efforts and are behind many commodity marketing campaigns, such as “Pork, the Other White Meat” and “The Incredible, Edible Egg.” Since there is little differentiating one bushel of corn from another, coordinating marketing efforts like this avoids a situation where one segment of the industry is financing most of the advertising while the rest of the industry benefits without putting skin in the game.

I propose to utilize this model to fund crop genetic conservation and plant breeding efforts. For every bushel of, say, potatoes sold by farmers, a small fee is assessed. This fee would then be split between two pools: a program to collect and conserve wild or heirloom potato genetics and a potato breeding program in the state where said farmer lives. This would create a built-in pool of funding to make important investments in the future of a crop and it matches such investments to crop demand. This would mobilize funding for conservation and breeding efforts for many neglected crops, especially fruits and vegetables.

Reform international food aid

A common trend in American government programming making is the muddling of desires of the agricultural industry with other policy domains. Energy policy becomes a program to subsidize corn farmers through biofuel mandates. Nutritional education campaigns overemphasize the importance of dairy in one's diet to improve milk sales. This mission creep is difficult to untangle, as the farmer vote and farm lobbyists are incredibly powerful in D.C. The one area of policy where this subsidy-seeking occurs that especially hurts my heart is international food aid.

The main program for distributing food aid to developing countries is Title 2 of the Food for Peace Act, which initially allowed for the distribution of food surplus owned by the federal government as humanitarian aid. This has evolved into the U.S. government directly purchasing foodstuffs from American farmers and distributing them to developing nations. The problem with this arrangement gets to one of the core issues of contemporary development strategies.

Donating food directly fulfills a temporary need but neglects an opportunity to utilize said funds for longer-term development. If the funds appropriated to Food for Peace were instead spent to purchase food in the nation experiencing food insecurity the demand stimulated would in turn stimulate investments. If farmers in affected regions knew they could score a U.S. government contract, they may invest in strategies to boost yields like irrigation or mechanization. In cases where the recipient nation is experiencing persistent famine or is truly unable to produce the necessary food, funds should still be spent regionally to better develop the infrastructure and capacity of regional breadbaskets and to build out some semblance of long-term sovereignty.

Under the current scheme, people are getting fed, which is great. However the muddling of international development with domestic agricultural needs means that the impact of the program for its recipients gets diluted to create yet another subsidy for the American farmers. Allowing these funds to be spent more effectively is a no-brainer for both the taxpayer, who sees their paycheck being put to better use, and the recipient nation who gets both immediate aid and an investment in the future.

Ultimately, there are many directions for agricultural reform in this country. These five by far not the only concepts for reform. Representative Pingree (D-Maine) introduced the Agricultural Resilience Act in 2023, which pursued similar outcomes by different mechanisms. But I do think these ideas would do a lot of good if properly fleshed out by folks better versed in economics and law than myself. Agricultural policymaking needs a big rethink, and a big aspect of that is turning away from this ‘throw cash at every problem’ approach. Structural remedies, with sustainable funding mechanisms rooted in agricultural markets, are the only way forward to transforming our farms for the better.

What I’m Reading, Watching, and Listening too

The Militia and the Mole: A gripping tale of how a random activist infiltrated a right-wing militia.

The Evolution of Avalanche Mitigation in Utah: When you’re no longer able to shoot mountains with cannons, how do you prevent avalanches?