Our Business is Making Money

The Destruction of our Fright Railways

Historically, railroads have been the backbone of American freight infrastructure. For every item being moved long distances, if it couldn't be done over water, it was taken by train. Trains helped build the banking, oil, and steel industries. The wealth that built our nation was moved from coast to coast and from the interior to port by a train. From this key economic position, train companies built one of the most infrastructure networks in the world and rose to become Titans of industry. Train companies were the tech companies of their day.

Oh, how far the mighty have fallen.

Train companies in the US are still quite profitable. But they are by no means what they once were. American railroading doesn't build new track, conducts bare minimum maintenance, and even gives up profitable lines of business. Companies like BNSF or Union Pacific act like they don't want to own any track in the first place. They act like they don't even like running a railroad.

Modern railroads pursue a model called Precision Schedule Railroading, or PSR. Essentially, they streamline freight movement through their system by creating longer trains using less track on fixed schedules. This reduces a lot of the system's resilience, as a schedule disruption will cascade across the network, spiking delays and interruptions. And because trains are so much longer and freight is centralized on fewer trains, disruptions have larger impacts on delivery schedules. All of this results in poor service and worse safety records.

Rail operators settled on this model in the pursuit of a metric known as an operating ratio. This statistic reports how much you must spend to earn $1.00 of revenue. The goal is, of course, to have the lowest possible ratio. However, the operating ratio is not the same as profitability. Businesses have a range of activities, each with its own operating ratio. A grocery store earns a lower operating ratio on bread and milk than for peanut butter or frozen pizzas. However, selling cheap staple goods attracts more customers, resulting in higher profits overall. The high ratio business activities are necessary for long-term business interests. IT and customer service departments hold a similar role in improving operational efficiency or retaining customers despite their high ratio.

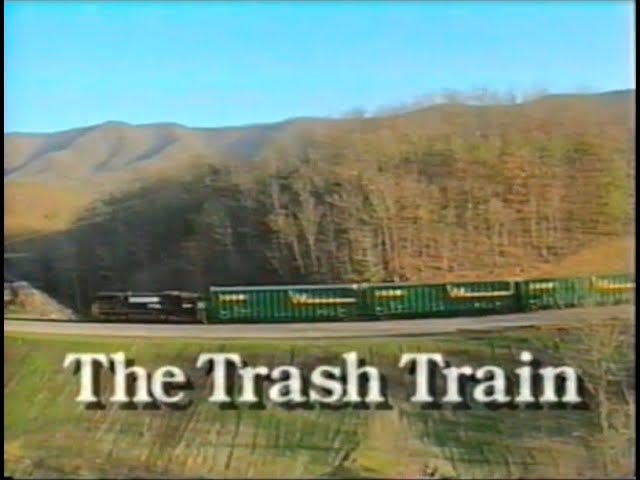

Railroads eliminate profitable business lines in pursuit of a better operating ratio. In Roanoke County, VA, Norfolk Southern dropped a profitable contract with the county government to move trash to the landfill. Despite being a consistent source of income, the deal required specialized cars and a dedicated crew, which proved more expensive than their core business. Despite still making a profit, the company wanted a better ratio and shut it down. Essentially, the management philosophy pursued by Norfolk Southern is cutting profitable enterprises that have outlier operating ratios. Even if there is no problem with them. Even if they provide a valuable service. This process leads to a continual atrophying of the business into its least common denominator version.

Now, Roanoke's garbage is moved by far less efficient trucks, causing inordinate traffic on overcrowded highways.

The kinds of contracts railroads want are ones moving bulk commodities. Take Wyoming coal country. These are long trains with the same cars moving from point A to point B on a consistent schedule. With scale like this, you can operate a business with very low operating ratios.

This is the business plan that railroads want. They will continue dropping profitable business lines in pursuit of contracts that fill this and only this model. They will only invest in infrastructure that fits this mold. The cost? Reliable, cheap, and low-carbon freight movement is no longer available to the vast majority of sectors. For the rest of us, if we want the reliable delivery of goods, we will have to get it through a truck, spending more money and blowing more carbon into the atmosphere.

This is not a business that is run by people who like railroads. Nobody involved here started as a mechanic or night conductor and worked up to CEO. The people idolizing operating ratios are MBA graduates who interned at McKinsey and started in the company as middle management. They probably actually see a railroad once or twice a year. This is an industry run by professional managers.

I recently visited the National Transportation Museum in St. Louis. I highly recommend it! While touring around, we saw a car designed for the bulk movement of vinegar. It was made out of wood (as vinegar would corrode a metal car quite quickly) and painted white to prevent the product from getting too hot and spoiling. It is a bespoke solution custom-made for a specific client. It was still profitable, but not wildly so. This kind of car ran on a railroad that cared about running a railroad. It was still run by cutthroat capitalists, but at the end of the day, they still cared about the business.

There is a reason you can only see a vinegar car in a museum.

No one wants to run railroads anymore. There isn't any pride in overseeing essential national infrastructure. The people running freight lines don't want to own them. The engineers and planners who desire to tackle exciting and technical problems and provide good service while making a healthy profit have been excised from leadership. All who are left in the driver's seat are MBAs with no attachment or interest in the industry they chose. This isn't good for the quality of service. It isn't good for the long-term health of our rail industry. And this pattern, replicated across sectors, is disastrous for the economy.

This pattern in the freight industry originated in the aftermath of World War 1. While it has historically been present in various tranches of the economy across history, the trend of management by financiers grew like a tumor in General Electric under Jack Welch and, once excised, spread the cancer across the economy.1

An Economic Malaise

GE was a behemoth—the epitope of the forgotten era of welfare capitalism. An age between World War 2 and the Reagan years when college was subsidized, the rich were taxed up to 90%, and union membership was at its peak. Workers at GE were all but guaranteed stable employment, a salary that could send two kids to college on a single income, and a healthy pension when they retired.

Jack Welch destroyed that.

Welch invented hyperfocusing on the quarterly earnings report. To clinch the coveted CEO spot, he cut staff and reduced the innovation budget in the division he controlled. This temporarily boosted its performance before the consequences of his actions could set in. Because of this, he was awarded the top spot, and he brought this model with him. In a short period, he realigned corporate strategy away from producing quality products and providing stability for workers. Instead, he wantonly cut jobs, offshored production, and ended investment in his workforce and innovation. The only division that received any investment was the credit division. Welch sold off or ended investment in anything with significant upkeep costs, like product design or quality control, despite them being the core of the business. He temporarily juiced profits through this pillage, but as the dust cleared, a titan of the industry was exposed to be a shell of its former self.

In 2018, GE was removed from the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the 30 top American companies. It was the last of the original 30 to be removed from the index.

This pattern has been replicated across the economy. All forms of manufacturing have followed this model, slowly hollowing out our productive capacity and the middle class. These are the same processes that destroyed Boeing. While I'm mainly talking about corporate culture in this post, institutional frameworks around corporate governance and anti-trust law are the environments that allowed this culture to thrive. This is why reigning in Wall Street and reviving anti-trust regulation is so important (one of the bright spots of the Biden presidency is FTC chair Lina Khan, who has been reversing a 40-year anti-consumer trend in government).

And while these institutional arrangements are ultimately more important, culture matters. It matters that the people running these companies are almost exclusively business school grads. It matters that engineers and workers are left out of the boardroom. American business of the 19th and 20th centuries was cutthroat, exploitative, and advanced imperial aims. It's not a model I want to return to. But I think the fact that people could rise from working on a production line to being the CEO of a major manufacturing firm says something about why my KitchenAid mixer has passed through three generations of my family. In many ways, the ruthless capitalists of the era still cared about providing functional goods and solving problems for the everyday American. They weren't wholly alienated from the production line, and management wanted to produce something worthwhile and long-lasting. This is a lesson we can learn.

What is to be Done?

One of the problems of the American economy is we've gone from companies that think 20 years into the future to companies that can only think to the next quarterly earnings report. And it's not simply just greed. People were just as greedy in the 1950s, the golden age of capitalism, as today. It comes down to institutions and incentives. It's about how we design productive units, how companies are owned and governed, and the incentives created by fast-moving equity and derivatives markets. No one is creating companies for durability because that is not what the stock market wants. Companies are destroying perfectly profitable and well-designed products because every quarter needs to be better than the last. That is not something that needs to be baked into the logic of the economy. We can have a growing and innovative marketplace without this.

Going back to freight rail, I think nationalization makes the most sense. Several unions have made that proposal, which would go a long way to getting things back in order. No longer beholden to short-term profits, a national rail company could establish a more comprehensive scheduling system and focus on reliability and infrastructural improvements. While I know that citizen confidence in government-run enterprises is quite low, many services are excellently run and continue to innovate in their space. For example, The National Weather Service constantly improves its models and develops new and valuable data products that undergird every weather forecast you see. The government can run dynamic enterprises.

More generally, increased worker and consumer stakes in enterprises that affect their lives are the direction that will get us out of this mess. Workers prioritize the long-term success of the enterprises they are part of as it is tied to their long-term economic stability for employment and pensions. Furthermore, workers take pride in their work and want to provide goods and services that are reliable, sustainable, and cutting-edge. Train engineers and system designers like trains and want to see the best-designed and implemented infrastructure possible. They'll still care about profit; they'll still care about long-term financial success and stability. But, having businesses that operate more democratically, such as cooperatives or highly unionized workplaces, would structurally imbue firms with a constituency in favor of these values.

Is that not an economy that you would rather live in?

McDonald's is a real estate company, Starbucks is a bank, and Warner Bros mothballed an entire movie for a tax write-off. This economy is not run by people who care about the businesses that they are in. That needs to change. We need people who care about their work and the goods and services they sell to take control of corporate America.

What I’m Reading, Watching, and Listening too

Weird election traditions around the world: A great video going into the election. My personal favorite is covering Susan B. Anthony’s grave with I Voted stickers.

The Atlantic Did Me Dirty: In a piece about literature education, the Atlantic flattened one educator’s opinions and experiences to fit the narrative that their writer went into the piece with.

In case you were wondering, GE is the gallbladder of the modern US economy. Incidentally, US Steel is the appendix, and we should have had an appendectomy and sold it to Nippon Steel, but instead, we decide to keep our diseased organs. Is this analogy getting tortured? You bet it is. Just like the American consumer.